the churchie 2022

-Artists: Darcey Bella Arnold (VIC), Emma Buswell (WA), Jo Chew (TAS), Kevin Diallo (NSW), Norton Fredericks (QLD), Jan Griffiths (WA), Jacquie Meng (ACT), Daniel Sherington (QLD), Linda Sok (NSW), Lillian Whitaker (QLD), Agus Wijaya (NSW), and Emmaline Zanelli (SA).

Curated by Elena Dias-Jayasinha

Cast your vote in the People's Choice Award via the VOTE HERE button below.

Read more about the churchie emerging art prize 2022 here.

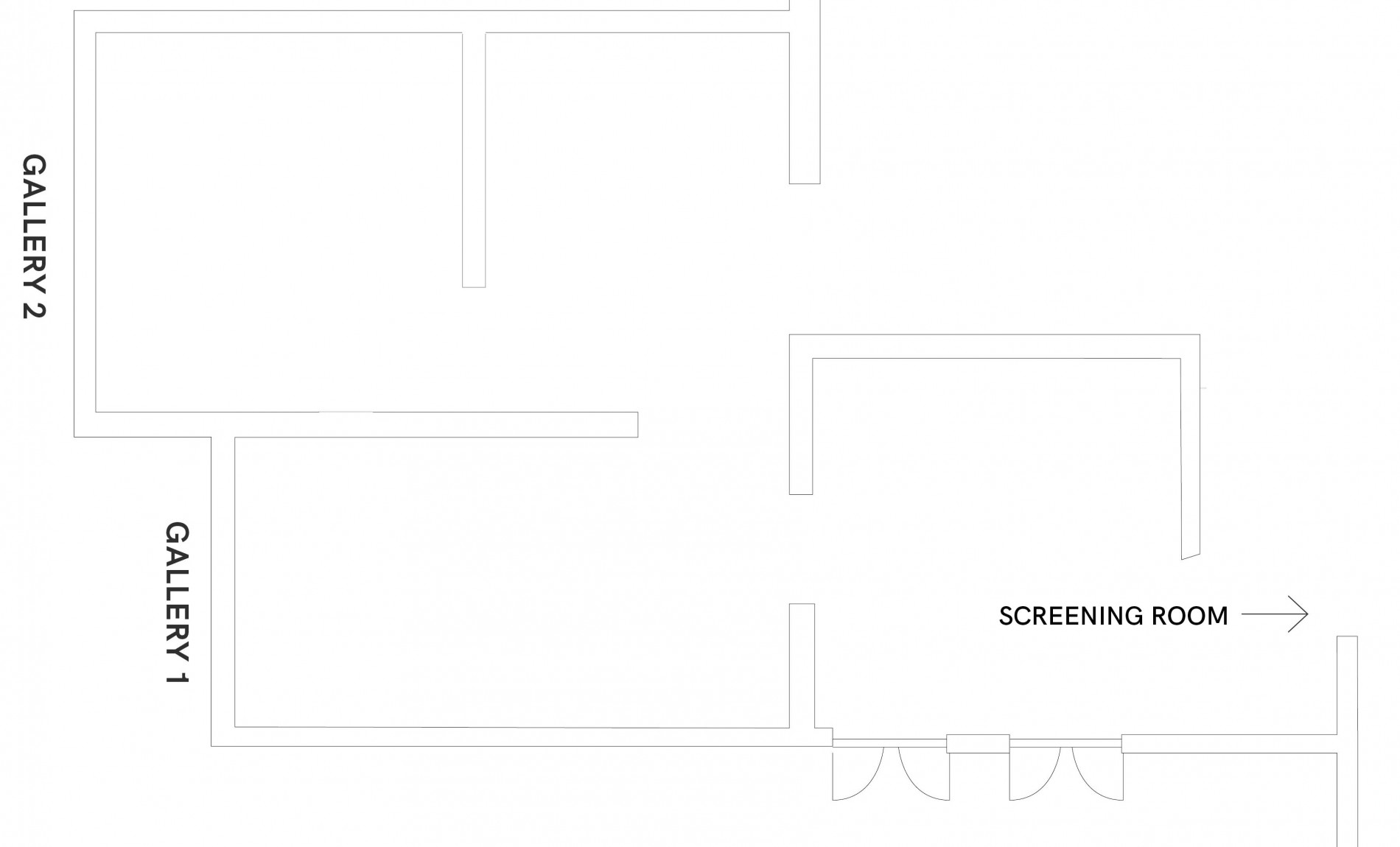

Gallery 1

| 1 |

Lillian Whitaker

Mutualisms, 2022, beeswax sculptures on hex-plywood plinths, dimensions variable. Lillian Whitaker’s interdisciplinary practice investigates ecological balance in the context of the Anthropocene. The artist works in collaboration with European honeybees, forming a mutualistic relationship in which both parties benefit, to create sculptural and digital work. In Mutualisms (2022), she presents three beeswax sculptures on custom plinths, accompanied by a subtle yet compelling soundscape. To create each form, Lillian placed manipulated wax objects into hives, upon which the bees were invited to build. The artist’s relationship with honeybees is rooted in an ecocentric framework that rejects the anthropocentric hierarchy of humans and nature. In Lillian’s practice, the ‘more-than-humans’ are bestowed agency and authorship as co-creators. |

| 2 |

Norton Fredericks

Identity Landscape, 2022, wood felt, silk, flax, botanical dyes, series of 3, (1) 164 x 188cm, (2 & 3) 45 x 195cm. Norton Fredericks is a fibre artist whose sustainable practice examines themes of identity and place. For Identity Landscape (2022), Norton gathered eucalyptus leaves from three places of personal significance: Tulmur/Ipswich, Meanjin/Brisbane, and Yugambeh/Gold Coast. He boiled the leaves to create natural dyes—or ‘extractions of landscape’—that were used to soak wool. Norton blended the wool together through wet felting, one of the oldest techniques used to create fabric. The resulting work features botanical prints and topographic lines, forming a biographic map that demonstrates the artist’s growing connection to Country. Fully sustainable, once Norton’s work reaches its natural end, it can be composted to return nutrients to the soil. |

| 3 |

Daniel Sherington

untitled (bullshit interior décor_v3, 2022, uv inkjet print on synthetic polymer resin, backlit with IKEA strip lighting and mounted on IKEA wall hooks, 70 x 80 x 8.5cm. Through drawing and digital processes, Daniel Sherington critically reframes Western conventions of artmaking, seeking to understand their value and contemporary connotations. In untitled (bullshit |

| 4 |

Jo Chew

From the walking house series: Tenderly, 2022, oil on canvas, 137 x 107cm. Moving, 2019, oil on canvas, 91.5 x 91.5cm. Strangers, 2022, oil on canvas, 122 x 122cm. For the dreamer, 2020, oil on canvas, 61 x 86.5cm. Jo Chew’s walking house series (ongoing) responds to experiences of displacement. Across the paintings, a figure carries a portable home over challenging terrain, inspired by the story of Liu Lingchao, the ‘Snail Man’. Lingchao gained attention for his portable house made from bamboo poles and plastic sheets. He carried the house on his back during three-day trips from his hometown Guangxi to the capital city Liuzhou, where he collected rubbish to sell for recycling. Drawing on this story, Jo explores the vulnerability of displacement but retains a sense of hope—she contemplates ‘home’ as a practice we carry instead of a physical place. The artist’s optimism is extended through process. Jo bases her paintings on small collage studies, whereby ‘exiled’ fragments are brought together into the ‘new home’ of the overall composition. |

Gallery 2

| 5 |

Jacquie Meng

spinning the coins of destiny while the devils play, 2021, oil on canvas, 100 x 140cm. in my room there are no rules, windows breathe fire and the floor dreams of water, 2021, oil on canvas, 77 x 122cm. somewhere in between worlds I am driving my truck and riding my horse, 2022, oil on canvas, 110 x 88cm. Jacquie Meng’s striking paintings emphasise diasporic cultural identity as multifaceted and ever-evolving. The artist presents three surreal scenarios using an intensely vivid palette. Each work contains references to Chinese mythology and folklore, Chinese children’s poems, I Ching divination, Taoist practices, urban architecture, and contemporary clothing including UGG boots and The North Face vests. While some elements are directly inspired by the artist’s personal experiences as Chinese-Australian diaspora, others are completely fictionalised. Jacquie seeks to highlight the infinite ways in which culture and spirituality can intersect to form one’s identity, rejecting the notion that diasporic cultural identity is limited to national and geographic categorisations. |

| 6 |

Darcey Bella Arnold

Ceci n’est pas une orange, 2022, oil on cotton duck, 80 x 90cm. Saffron, 2022, acrylic on cotton duck, 150 x 200cm, with American red oak stand (totaling 227 x 210 x 60cm). Darcey Bella Arnold’s practice examines the relationship between language, pedagogy, colour theory, and art history. Her sculptural installation comprises two paintings – Ceci n’est pas une orange (2022) and Saffron (2022) – mounted on a custom-built American red oak stand. In the former painting, two oranges are illustrated above a French phrase meaning, ‘This is not an orange’. Language is the authority in the work. There is a pictorial image of two oranges, and this is denied by the sentence. Inspired by René Magritte’s The treachery of images (1929), Darcey uses visual language to affirm the authority of language, but also emphasise its arbitrary nature. Her second painting, Saffron, extends upon this idea by offering an additional way in which to comprehend ‘orange’ as a colour. |

| 7 |

Emma Buswell

After Arachne, 2020, wool yarn, metallic thread, hand knitted cardigan, beanie, and handmade counterfeit Gucci cardigan. Emma Buswell’s After Arachne (2020) is an example of the artist’s distinct textile practice, which draws on handicrafts and knitting techniques passed down from her mother and grandmother. Arachne in Greek mythology was a mortal woman who challenged Athena, goddess of wisdom and war, to a weaving competition. In her tapestry, Arachne depicted instances of the gods abusing mortal women’s rights, causing Athena to become enraged. In disgrace, Arachne hung herself and was later transformed into a spider, bound to weave forever. Arachne’s story presents weaving, knitting and other textile practices as some of the first actions available to women to contest systematic oppression and violence. Emma’s work seeks to intuit this sensibility and in doing so, exorcise the events of 2020 through knitting. Her wearable artforms represent major events, both personal and political, that occurred each month of the year. Together they form a tapestry of anxiety, frustration, humour, grief and reflection. |

| 8 |

Linda Sok

Salt Water Deluge (Tucoerah River), 2021, Cambodian silk, water collected from Georges River, salt, rattan, 210 x 330 x 80cm. Linda Sok’s Salt Water Deluge (Tucoerah River) (2021) speaks to preserving Cambodian culture and healing in the aftermath of the brutal Khmer Rouge regime. The textile installation was created in collaboration with the artist’s sister Solina, and comprises 27 silk strands hung on rattan frames. Silk weaving has been part of Cambodian culture for centuries, passed down through matrilines. It was one of the many art forms targeted during the Khmer Rouge regime, and came close to being erased. Linda seeks to preserve this practice, dipping each strand in a saline solution using a method similar to how her parents pickle vegetables. Harnessing the curing properties of salt and water, the artist acknowledges how trauma embeds itself within objects and individuals, and endeavours to take remedial action. Linda’s approach is not to employ shock tactics, but rather, to use ‘soft aesthetics’ to create a safe space for contemplation and remembrance. The water used in this work was collected with permission from Darug Elders. |

| 9 |

Agus Wijaya

Jejadian, 2022, mixed media installation, dimensions variable. Procession, 2020, archival pigment printed on art canvas and mixed media, mounted on perspex, 86.2 x 142.4cm. Taksakala, 2021, archival pigment printed on art canvas and mixed media, mounted on perspex, 43.1 x 71.2cm. Agus Wijaya explores cultural and self-identity through a practice spanning digital design, 3D printed sculpture and installation. Growing up in Cianjur, a small village in the Indonesian province of West Java, Agus was subject to prejudice for his Chinese heritage. Since Dutch colonisation, an open mistrust and violence towards Chinese Indonesians has existed. Being told he was not ‘real’ Indonesian, Agus became disconnected from his home country. In his art, he felt unable to draw from Indonesian or Chinese characters. Eventually, in an act of defiance, he developed his own visual lexicon as a way to reclaim his identity. His surreal figures and motifs feature in prints Procession (2020) and Taksakala (2021), and sculpture Jejadian (2022). All three works were created through digital media, a method that has also faced bias for not producing ‘real’ art. Agus employs a hypersaturated red-green palette, giving each work the semblance of an anaglyph image. With both red and green required to render such images complete, the artist encourages us to celebrate the parts that make up the whole, perhaps a metaphor for him reconciling the cultures that form his identity. |

| 10 |

Kevin Diallo

From the Ode To Zouglou series: Zigbo, 2021, acrylic paint on pigment printed cotton canvas, 63 x 90cm. Au Maquis, 2021, acrylic paint on pigment printed cotton canvas, 63 x 90cm. Mouho, 2021, acrylic paint on pigment printed cotton canvas, 63 x 90cm. Botcho, 2021, acrylic paint on pigment printed cotton canvas, 63 x 90cm. Kevin Diallo’s Ode to Zouglou (2021) investigates music as a platform for cultural connection. Each print features an enlarged screenshot of a Zouglou dance clip from YouTube, and is superimposed with hand-painted designs inspired by West African mud cloths. Zouglou is a dance-oriented style of music that emerged from the Ivory Coast in the mid-1990s. During the pandemic, Kevin reconnected with Zouglou to maintain and transmit culture, while physically isolated from family and community. YouTube played an important role in facilitating his embrace of Zouglou, and through his work, the artist recognises how digital platforms provide cultural access to those living in diaspora. |

| 11 |

Jan Gunjaka Griffiths

History Beneath the Beauty, 2022, natural pigment on paper, porcelain with underglaze, glaze, 171 x 228 x 3cm. Courtesy Waringarri Aboriginal Arts. Jan Gunjaka Griffiths maintains personal family narratives through a practice spanning ceramics, painting and installation. Her most recent series History Beneath the Beauty (ongoing) draws on the stories of her grandmother. Jan shares: “Woorrilbem holds a history. A blast from my grandmother’s past. As a child she went to this billabong to collect the lily flowers—its bulb, mussels and other edible bush food—to take back to her family. One particular day on a usual walk she saw two strange men way off in the distance. A manager on horseback and a black tracker leading a donkey with a sack on its back. They were tracking Aboriginal, Miriwoong people to work for the manager at the station. As the men came closer, my grandmother slipped into the billabong to hide until the men were out of sight. My grandmother then got out and started running as fast as she could back to her family, but it was too late as the strange men were already approaching the camp. With mixed emotions my grandmother spoke and pointed at the same time to the strange men, but the black tracker spoke in Miriwoong language and said they were friendly people looking for workers to work at the station for sugar, tea and tobacco as rations and brought flour to make bread as a peace offering. Some Miriwoong people did go to work for the strange manager man. My grandmother and her family stayed on Country. If we don’t carry this story and tell our children the history of Woorrilbem and its beauty…my grandmother’s Country, will be lost and forgotten forever.” |

Screening Room

| 12 |

Emmaline Zanelli

Dynamic Drills, 2020-21, three-channel video, surround sound, 00:31:00. Emmaline Zanelli’s Dynamic Drills (2020-21) speaks to the production and transfer of memory. The three-channel video work features the artist and her Nonna Mila performing ritualistic actions that recall the repetitive gestures found in manufacturing. Mila had a diverse career in manufacturing, beginning as a knitting machine technician in Italy, before emigrating to Australia and working at a wool processing plant and a factory for shrink-wrapping poultry, among other industries. Through her work, Emmaline seeks to dissect the relationship between the body and the machine, and connect her Nonna’s work history to her own labour as an artist. In a voiceover, Mila recites excerpts from Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurism (1909). Futurism was an early 20th century avantgarde movement that emphasised rapid progress and the technological triumph of humanity. Performing both futile and functional actions, Mila and Emmaline move between rejecting the Futurists’ mechanical dreams and somewhat fulfilling them. |