Khadim Ali

Invisible Border

-Khadim Ali is one of Australia’s most acclaimed artists, known for his masterful works that poetically explore the experience of displaced people across the globe.

A member of the persecuted Hazara ethnic minority, Ali is the third generation of his family to be exiled from his homeland of Afghanistan. Born and raised in Quetta, Pakistan, Ali studied traditional miniature painting at the prestigious Lahore National College of Arts, before migrating to Australia in 2009.

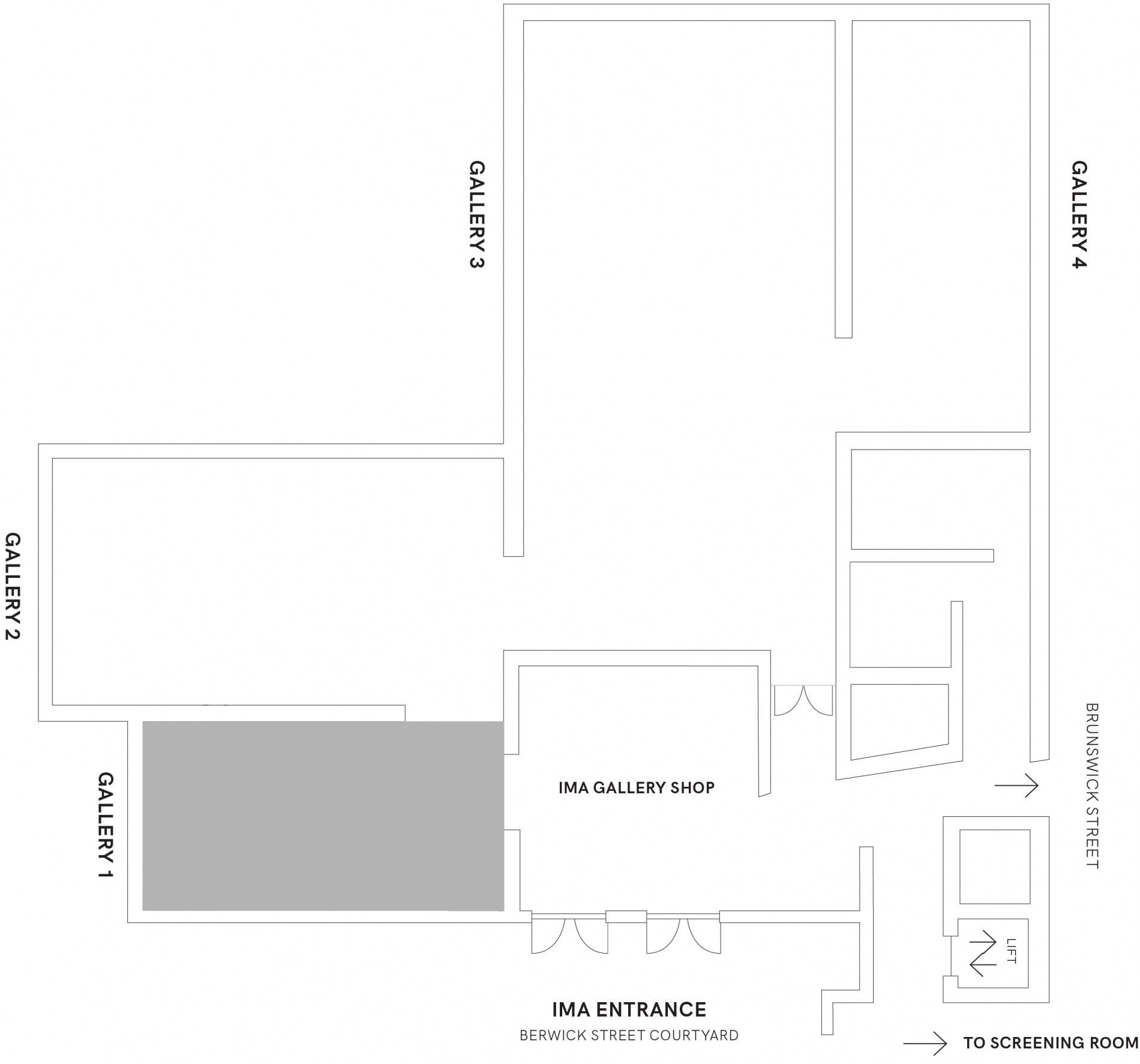

Invisible Border is the artist’s largest ever solo exhibition in his adopted country. Comprising sound installation, miniature painting and intricately constructed textiles, the exhibition features new works that have been created in collaboration with a community of men and women in Afghanistan, some who have lost family members in war.

Ali’s interest in tapestries developed soon after his parents’ home in Quetta was destroyed by a car bomb. Amongst the rubble and debris left from the blast, a collection of rugs and weavings remained the only items intact: miraculously able to withstand the reign of terror inflicted upon his family and community. In these new large-scale tapestries, Ali makes comment on war, geo-politics and personal trauma, drawing from a range of historical and contemporary influences including the recent Black Summer bushfires, Persian literary masterpieces, children’s fables and the Mughal Dynasty.

Expressing the profound horror, grief and loss experienced under modern-day warfare, Invisible Border is a necessary and vital exhibition during a time where political propaganda, violence, and fear pervades global relations.

This exhibition guide can be read in English here and in Farsi here.

Gallery 2

| 1 |

Khadim Ali

Sermon on the Mount, 2020 Since relocating to Sydney twelve years ago, Ali has begun incorporating quotidian Australian iconography such as eucalyptus, currency and kangaroos into his work. Sermon on the Mount (2020) is an example of the artist’s evolving visual language. A direct response to the 2020 Black Summer bushfires—which devasted much of Australia’s bushland—the work depicts a cast of animals and mythical creatures seeking refuge atop a mountain engulfed in flames. The title of the work, Sermon on the Mount, makes direct reference to a series of teachings attributed to Jesus Christ, and widely considered to contain some of his most important messages. |

| 2 |

Khadim Ali

Untitled 1 (from Sermon on the Mount series), 2020 After graduating from art school in Pakistan, Ali quickly gained global attention for his masterful miniature paintings that combined traditional techniques with contemporary subject matter. Inspired by his grandfather, who was a Shahnameh singer, Ali’s early works drew parallel between the plight of exiled people and the angels and demons found in the Book of Shahnameh, a Persian literary masterpiece comprising of 50,000 couplets and written between c. 977 and 1010 CE. |

Gallery 3

| 3 |

Khadim Ali

Invisible Border 4, 2020 In the exhibition’s most overtly political work, Ali directs his aim at the global leaders profiting from the twenty-year long war in Afghanistan. Invisible Border 4 (2020) takes inspiration from Jahangir, the fourth Mughal emperor of India, who ruled from 1605 until his death in 1627. On the occasion of his son Khurram’s fifteenth birthday, the Emperor ordered the young Prince to be weighed in gold and silver coins. Depicted in numerous classical paintings, including one held in the collection of the British Museum, Jahangir then distributed the coins to the poor. |

| 4 |

Khadim Ali

Invisible Border I, 2020 In the wake of Donald Trump, fake news, and social media, our world has never been more polarised. Invisible Border I draws attention to this growing divide, comparing a historical example of tolerance to our present-day, and increasingly common, expression of difference. In vivid technicolour Ali recreates an illustration of a Hindi religious story that was commissioned by a Muslim sultan, despite his opposing faith. Unfolding beneath this lively tableau of demons, gods and mortals is an ominous and violent scene depicting Christian and Muslim men mid-conflict. A work that perceptively addresses our rising intolerance of one another, Invisible Border I recollects a time where difference was met with benevolence. |

| 5 |

Khadim Ali

Invisible Border 1, 2020 The largest tapestry in the exhibition, Invisible Border 1 (2020) draws pictorial inspiration from Afghan war rugs, a popular ‘tourist’ item sold to international troops. Emerging during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the late 1970’s, war rugs draw on the country’s long-standing tradition of weaving to produce contemporary designs that portray the apparatus of war. Coveted collectors’ items, war rugs continue to be manufactured to this day, and chart the ever-advancing technology of warfare in the Middle East. Recent rugs, for example, incorporate drone elements and scenes from the September 11 attacks. |

Gallery 4

| 6 |

Khadim Ali in collaboration with Sher Ali

Urbicide 2, 2020 Urbicide is a term that translates to ‘violence inflicted upon a city’. Taken from the Latin words ‘urb’ (city) and ‘cide’ (to kill), the expression is often used to describe rapidly changing urban environments in the age of globalisation and late-stage capitalism. In Ali’s Urbicide 2 (2020) the destruction of a city is framed within the context of the global war on terror. |

Sermon on the Mount by Khadim Ali and Asad Buda

A group of animals took refuge in the mountains from the fire that had burned and destroyed their homes. They gathered at the foothill of the mountain to find a solution for their survival. The koala that was affected the most by this catastrophe went up the mountain and delivered a speech as follows:

‘I have no good news for you. I have come to inform of the great extinction. I am the voice of the earth: the voice of this common mother, who will soon be destroyed from many wounds.

There have been wounds to the earth for countless centuries. They are inflicted by the fiercest enemies with hearts full of extravagance, resentment and revenge. These enemies think they have been banished from the imaginary world. To return to the imaginary paradise, they have turned the earth into hell.

Woe to the earth whose destiny is in the hands of human beings that have launched all-out attacks against this common home. They burn the forests, pollute the water, blow up the mountains, massacre the trees and turn the forests to ashes. Their factories are active the world over. Their traces of crime are evident everywhere: on land, in the seas and in the earth's atmosphere. The snow on the peaks has melted. Thick polar ice has cracked and is collapsing piece by piece. Humans now occupy our territories. They eat our meat. Our skin is sold in the market. In response to their complete domination and our consequent subjugation, most of us have been forced to retreat into the dwindling habitats in which we can survive. Those of us who do not suffer death or become domesticated or are arrested, imprisoned and sent to camps and prisons they call zoos.

Humans think they have a sublime nature and are of a superior race. They believe animals have no right to life and deserve to be killed. The ancestors of man, have commanded to sacrifice animals before the gods. Even though we koalas are satisfied with the leaves of the tree and drink less than our share of water, a large population of us have died due to lack of water and food. This sacrifice from us is on the rise. Our extinction is near. Worry about your tomorrow! Worry about where to take refuge. Worry about the future of your children!’

The animals’ panic multiplied as the koala finished her words. On the other side of the mountains, forests were burning in the fire. A large group of animals that were supposed to accompany the koala on their way back from the mountains dispersed and fled. The youngest child of the koala, unaware of the human brutality that recently caused extinction of their neighbor, the Thylacine (Tasmanian tiger), was asleep in a branch of eucalyptus leaves. He was an infant that had not developed his sight to see the man drilling wounds on the face of the earth. He fainted in the toxic smoke, and did not even know that his mother had gone to the mountains to deliver a sermon. The flames grew louder by the minute, and the fire became widespread.

As his mother reached the tree it caught fire. Though desperate to escape, the last koala and her baby were engulfed in the flames. Other animals watched the trees burning and turning to ashes from a distance, shouting, indeed, that she was the true voice of the earth, informing the great extinction of humankind. Truly man is the executioner of life. Our killer, the killer of the earth and the killer of themselves. The hands of this murderer are stained with the blood of the earth and the end of this horrible crime is not only the end of our lives, they thought, but the annihilation of human life itself.

Urbicide by Asad Buddha

There is a dystopia, within each one of us

A beheaded Kabul

A Tehran with many prisons

An Islamabad overflowing with terror schools,

A Baghdad with twenty-four thousand mad caliphs,

A Bamiyan without Buddhas

An Aleppo full of corpses

And the Mediterranean with thousands of refugees.

I was born a stranger, from my mother’s womb

A demon child: abandoned by my father to the Alborz’s mountains to be eaten by animals,

The animals, however, were kind

I was given shelter and food,

Fed from deer milk

Warmed by Simorgh wings

Comforted in the entire Alborz mountain

Yet, the innocence of Alborz dismayed me

Because I was a human being

From centuries wild heritage

My heart reminded me of the human world;

I returned to Kabul from Mountains

Right from the start the city taught me how to throw stone at windows,

At birds, at butterflies, at cats, at dogs and at strangers.

Stoning of Rudabah’s beautiful eyes, who looked at me lovingly from behind the window, was obligatory and rewarding.

To become expert in killing,

I was sent to religious schools,

In my school book E was for execution

B for bomb and bullet, G for gun and looting,

J was for Jihad,

K for Kalashnikov and killing of the city,

R for rocket

Q for Quran and G genocide

M for Mohmmad, mother bomb, Missile and massacre.

I learned the Alphabet, with the taste of paradise angels’ breast, who was flying in the sky of our muddy schools.

I started reading from a holy book, with the Taste of Thousands of imaginary naked women, they swam across the rivers of wine and milk, smoked hash with God and Prophets,

It was possible to have all these blessings if I could destroy cities,

Could erase humanity from my mind and soul

And became one like them.

Life had only one meaning: faith and kill.

Genocide and massacre were not enough,

I had to destroy cities, diversities and everything that embodied civilizations

Long before the war began, centuries before Soviet troops arrived in Afghanistan, I repeatedly destroyed and had ruined Kabul and Bamiyan, in my imagination,

Every morning and evening

In each Surah

In each verse

In every line and words of Quran,

I grew up,

Bullets and rockets took the place of stones,

I shot all the bullets in the Almond eyes of Rudabah.

Until no eyes no longer watched me from behind the windows,

Out of fear, we closed the windows

Now Kabul is a ghost city

And speaks with the language of the dead, smoke and fire,

حی علیالفلاح!

Again, another suicide in the city,

One of my classmates is determined to go to heaven; to sleep with the promised virgins,

Bones fly in the air,

Corpses dance awkwardly

And I am thrown into a terrible sea of blood and bodies

Verses of darkness, migration, and massacre

Darkness is everywhere,

Houses have no Windows,

People have no eyes,

I have no eyes,

The blindness runs the city, the citizens, myself and everything else.

Kabul is a Rudabah, where Mohammed go to night journey from the ladder of her hair,

His caliphs to the heaven,

And the twelve holy cows to Garden of Eden,

Kabul is a Rudabah where the Afghan honour, covered her beauty under mud, dust and Burqa,

Islam stoned her

Colonisers looted her,

And communists claimed her as their personal capital,

Mujahideen shot their faith with Kalashnikovs in her eyes,

Taliban beheaded her on the road,

And the liberals burned her in public.

Kabul is the city of blinds

The city of the one-eyed Amir al-Mu'minin

In this city development is a manual bomb,

Justice is a project,

Human right is an industry,

Fraud is the meaning of Democracy,

And the demonised persons are painters and poets try in vain to keep the stones and guns out of Rudabah’s eyes,

Everything follows the law of destruction,

Even poetry, prose and painting.

Every poem is a ruin,

Every prose is the chine corpses,

Every poet a captive demon who writes not to be killed,

And every painter is a wounded eye,

Tahminah, who has coloured her lips with Sohrab’s blood

Every painting is a pain,

A dark house without any windows,

Rakhsh’s torn belly in the middle of a well of corpses,

Poetry, prose and painting say nothing,

They show nothing,

Centuries of hideous falls of human beings in a hell called Kabul.

Kabul is Aleppo

She is Damascus

She is Baghdad

She is the battlefield of the holy cows

The bloody fingers of the painter cannot make it colourful,

Cannot hide the mass graves and ruins from her face,

It is impossible to heal the wounds of the Bamiyan mountains with colour and poetry,

Only the bullets and rockets of schoolbooks are screaming in the ear of the last ruins of Palmyra,

And it is the Kalashnikov that spills children blood on the walls of homes in Kabul,

There is a destroyed city, within each one of us

A ruined city where houses windows are attacked with stones at least five times a day by prayers,

I do not write poems,

I don’t sing,

I don’t read,

I do not draw any dream,

From Kabul to Damascus, I pile up the dead bodies,

Words are nothing against stones and guns,

Paintings cannot wash the bloody earth

It will take centuries for the earth to give birth to Bamiyan mountain.

And the Middle East is too wounded to give birth to the Palmyra once more.

If I sometime scratch the heart of paper,

If I sometimes wash red-coloured paper in Klarälven,

It’s because I am committed to diversity, to the earth as it was without any political borders,

And the displaced did not die on the roads or at sea

If I sometimes take refuge in words,

It’s because I have nostalgia of the future,

Nostalgia of Alborz mount

Nostalgia of mother deer,

Nostalgia of Simorgh wings warmth,

Nostalgia of dead refugees on roads and seas,

Nostalgia of Gulbigum, Tabassom, Leyla, Amina and Saheb-dad.

The nostalgia of reading the diary of the beautiful Rudabah,

Who was watching me from the windows and how stupidly I threw stones at her beautiful almond eyes.

About Khadim Ali

Born 1978 Quetta, Pakistan

Khadim Ali currently lives and works in Sydney, Australia. After growing up in Pakistan as a member of the persecuted Hazara community, Ali was trained in classical miniature painting at the National College of Arts in Lahore before obtaining a Master of Fine Arts from the University of NSW.

Selected exhibitions include the Venice Biennale (2009); Safavid Revisited, British Museum, London; APT5, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane (2006); No Country: Contemporary Art for South East Asia at the Guggenheim New York (2013); Documenta (13) (2012); Rendezvous, Biennale de Lyon (2017), Lyon France; The National (2017) Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney; and Dhaka Art Summit (2018). Ali’s work is held in the collections of the National Gallery of Australia; Australian War Memorial; Art Gallery of New South Wales; QAGOMA, Brisbane; Victoria and Albert Museum, London; and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Khadim Ali is represented by Milani Gallery, Brisbane.

Acknowledgements

Invisible Border 1 and Invisible Border I forms part of Otherness, which has been developed in partnership with the Lahore Biennale Foundation. This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.